The Magazine of the American Landowner is an essential guide for investors, landowners, and those interested in buying or selling land. The award-winning quarterly is known for its annual survey of America's largest landowners, The Land Report 100.

Issue link: https://landreport.epubxp.com/i/822507

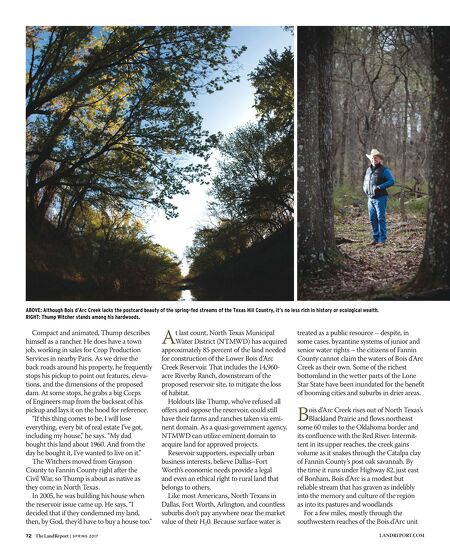

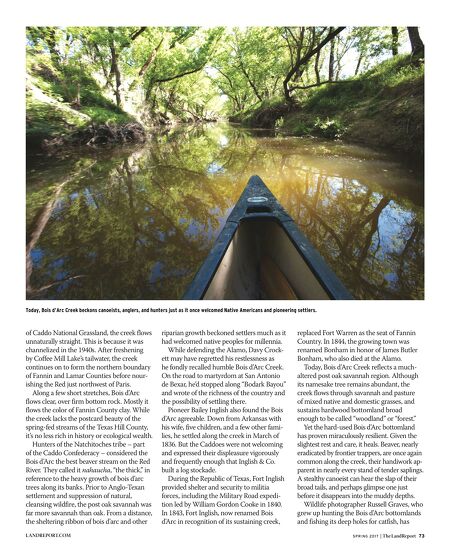

72 The LandReport | S P R I N G 2 0 1 7 LANDREPORT.COM Compact and animated, Thump describes himself as a rancher. He does have a town job, working in sales for Crop Production Services in nearby Paris. As we drive the back roads around his property, he frequently stops his pickup to point out features, eleva- tions, and the dimensions of the proposed dam. At some stops, he grabs a big Corps of Engineers map from the backseat of his pickup and lays it on the hood for reference. "If this thing comes to be, I will lose everything, every bit of real estate I've got, including my house," he says. "My dad bought this land about 1960. And from the day he bought it, I've wanted to live on it." The Witchers moved from Grayson County to Fannin County right after the Civil War, so Thump is about as native as they come in North Texas. In 2005, he was building his house when the reservoir issue came up. He says, "I decided that if they condemned my land, then, by God, they'd have to buy a house too." A t last count, North Texas Municipal Water District (NTMWD) has acquired approximately 85 percent of the land needed for construction of the Lower Bois d'Arc Creek Reservoir. That includes the 14,960- acre Riverby Ranch, downstream of the proposed reservoir site, to mitigate the loss of habitat. Holdouts like Thump, who've refused all offers and oppose the reservoir, could still have their farms and ranches taken via emi- nent domain. As a quasi-government agency, NTMWD can utilize eminent domain to acquire land for approved projects. Reservoir supporters, especially urban business interests, believe Dallas–Fort Worth's economic needs provide a legal and even an ethical right to rural land that belongs to others. Like most Americans, North Texans in Dallas, Fort Worth, Arlington, and countless suburbs don't pay anywhere near the market value of their H 2 0. Because surface water is treated as a public resource – despite, in some cases, byzantine systems of junior and senior water rights – the citizens of Fannin County cannot claim the waters of Bois d'Arc Creek as their own. Some of the richest bottomland in the wetter parts of the Lone Star State have been inundated for the benefit of booming cities and suburbs in drier areas. B ois d'Arc Creek rises out of North Texas's Blackland Prairie and flows northeast some 60 miles to the Oklahoma border and its confluence with the Red River. Intermit- tent in its upper reaches, the creek gains volume as it snakes through the Catalpa clay of Fannin County's post oak savannah. By the time it runs under Highway 82, just east of Bonham, Bois d'Arc is a modest but reliable stream that has graven as indelibly into the memory and culture of the region as into its pastures and woodlands For a few miles, mostly through the southwestern reaches of the Bois d'Arc unit ABOVE: Although Bois d'Arc Creek lacks the postcard beauty of the spring–fed streams of the Texas Hill Country, it's no less rich in history or ecological wealth. RIGHT: Thump Witcher stands among his hardwoods.